for what we're trying to get out of the experience. Taken together, they are filled with awe, inspiration, fear, joy, song, dancing, chest-beating, sadness, reflection, vulnerability, strength, warmth, solitude, and celebration. We're all over the map!! One of the things this brings to mind for me is something I like to say to people with some regularity: The term "Organized Religion" is an oxymoron.

When we organize something and ritualize it, we make it work for a whole group of people. We give it structure, predictability, order. And the word "religion," to me, refers to each of our personal, unique, individual relationships with God. So they are sometimes quite contradictory. But sometimes we need one, and sometimes the other. When we come to shul on the High Holidays, we look for familiar tunes that we can all join in on - Avinu Malkeinu, Ki Anu Amecha, Ha-Yom - and we listen for prayers that tell us we're in the Days of Awe, like Kol Nidrei and Un'tane Tokef. But the Season of Repentance should also include moments of personal reflection, introspection, and remembrance of loved ones. We pivot back and forth between communal, public experiences, and quiet, internal contemplations.

There's no one, single way to do this. And there's no one, ubiquitous emotion you should be feeling right now. Perhaps this year you are more in the mindset of Simchat Torah, needing to dance, shout, and express joy. Or maybe you feel

moved by the Yizkor remembrances and the Eileh Ezkerah, which remind us of the pain of past generations of our ancestors. Or you're somewhere between those two. Regardless, your High Holiday experience isn't going to be exactly the same as the woman sitting next to you, or the man six rows behind you. And none of you, of us, may feel wholly transformed by the liturgy. That is all ok. Just find your place in the hubbub of it all, physically and emotionally. Reflect on where you yourself are right now, and where you might fall along the spectrum from "organized" to "religion," or from Rosh Hashanah to Simchat Torah. Somewhere in all of it, waiting to be discovered, is you.

May you find meaning in this Season of Repentance. May you experience peace, inside and out, and harmony among all the parts of yourself that are vying for attention. Allow yourself to accept that this is an imperfect process, simply because we are all imperfect, struggling, messy, improving, wonderful beings. Be compassionate with yourself, and kind and forgiving with others. Challenge yourself to be a part of something, to invest and commit; but push yourself also to make room for your own needs, as well as some alone time. And every once in a while, give yourself a "should-less" day. May you obtain all parts of our holiday greeting: a Happy, Healthy, and Sweet New Year.

Shanah Tovah!

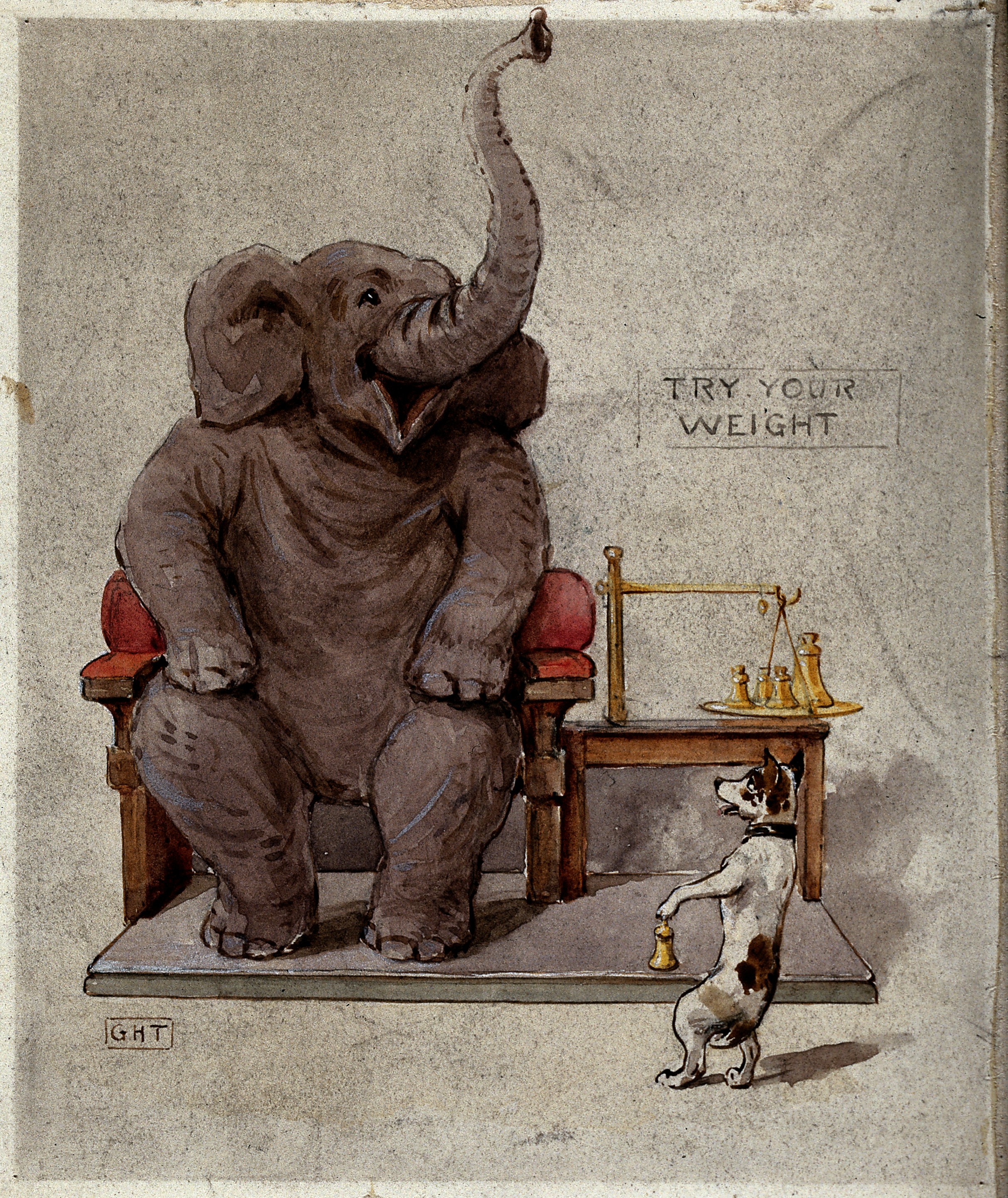

Photos in this blogpost:

1. CC image courtesy of יעקב קירש on Wikimedia Commons

2. CC image courtesy of Geagea on Wikimedia Commons

3. CC image courtesy of Itzuvit on Wikimedia Commons

4. CC image of "Co-exist" bumper sticker courtesy of Integral Church on Wordpress